What if some forms of dissociation are not about protecting against overwhelming emotion at all?

I recently read a 2025 paper by Anne Alvarez titled Dissociation: Defense and/or Deficit in the Making of a Pseudo Self, and what struck me is how Alvarez describes a group of people who often “do well” in therapy by conventional standards, but something doesn’t quite land. These folks are articulate and reflective, yet the work falls flat. Sessions depict engagement without aliveness.

Alvarez marks this clinical presentation as indicative of dissociation organized around absence rather than terror. She is describing patients whose difficulty is not defending against feeling, but what she refers to as a lack of access to emotional experience itself. What Alvarez offers is a way to distinguish between dissociation that switches on in response to threat and dissociation that emerges from a pervasive absence of emotional contact.

Many conventional trauma frameworks teach us to understand dissociation as a protective response from threat. The subjective experience becomes overwhelming, so the system pulls away and fragmentation follows.

That explanation fits many trauma histories involving chronic threat. But Alvarez asks an interesting question: What if there is nothing to defend against? What if the problem is not that feeling is too much, but that feeling never had the chance to fully develop? Her writing suggests that some people do not dissociate from experiences; they actually never fully arrived into their experiences. Early relational environments failed to support shared attention, curiosity, and emotional meaning. Over time, the system adapted by staying distant from feeling altogether.

What Alvarez offers is a way to distinguish between dissociation that switches on in response to threat and dissociation that emerges from a pervasive absence of emotional contact.

Alvarez draws on Winnicott and Bollas to describe what she calls a pseudo self or “as-if” personality. She notes an “as-if” quality to these presentations, where emotional life is organized around performance rather than lived experience. The pseudo self is adaptive and knows how to perform emotional life. It understands what feelings are supposed to sound like. It can participate in relationships. What it lacks is an energetic life force.

Many trauma survivors recognize this immediately. You can talk about emotions, but you don’t quite feel them. You can reflect on relationships, but something feels distant. You may even wonder why therapy keeps circling without landing. One of the gravest mistakes a therapist can make in these situations is to misread this as resistance, as it only deepens shame and makes you believe that something is wrong with you for not accessing what others seem to reach so easily.

An important idea in Alvarez’s paper is that feelings become meaningful when they are shared. Alvarez emphasizes that emotional experience depends on having someone there to receive and respond to emotional communications. Emotional experience develops through being seen, responded to, and held in another’s mind.

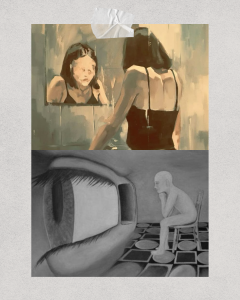

When early caregivers are emotionally absent, depressed, or mechanically responsive, feelings may not organize into anything coherent or understandable. A child may feel a flicker of excitement, fear, or sadness, but there is no one there to notice it, name it, or respond. Sensation rises and it goes nowhere. Curiosity starts to fade, whether that be curiosity in others, in the external world, or about one’s own internal experience. Over time, disengagement becomes the adaptive response. Alvarez conceptualizes this as dissociation born not from terror, but from nothing happening.

For survivors, this reframes chronic dissociation in a way that is often deeply relieving. You are not broken for not feeling enough. You adapted to an environment that did not cultivate your inner emotional world.

One of the gravest mistakes a therapist can make in this situation is to misread this as resistance, as it only deepens shame and makes you believe that something is wrong with you for not accessing what others seem to reach so easily.

Alvarez is clear that traditional insight-focused approaches often fail here. If therapy assumes that feelings are present but defended, it may push for memories, interpretations, or breakthroughs that simply are not accessible yet. The result is often more deadness. This is because the capacity for felt experience needs to be built before it can be explored.

The work here is very subtle. Gentle curiosity, flickers of interest, or small emotional shifts all become new moments of contact. Alvarez emphasizes the importance of the therapist’s emotional presence in this process. Distance and neutrality in the therapist are not helpful here. Instead, a therapist who is real, responsive, and attuned to what’s unfolding in the room is at the heart of the work. The work becomes about noticing and supporting emerging experiences within the client before trying to analyze them. In trauma language, this is about building affective capacity and presence before any kind of processing can occur.

The work here is very subtle. Gentle curiosity, flickers of interest, or small emotional shifts all become new moments of contact.

Some people dissociate because their systems learned to shut down in the face of threat. Others dissociate because no one was there to help them come online. Both are real and deserve care. If you have felt stalled or untouched by therapy despite doing everything “right,” this may offer a different perspective. Healing does not always look like remembering what happened. Sometimes it looks like discovering what it feels like to be emotionally alive for the first time.